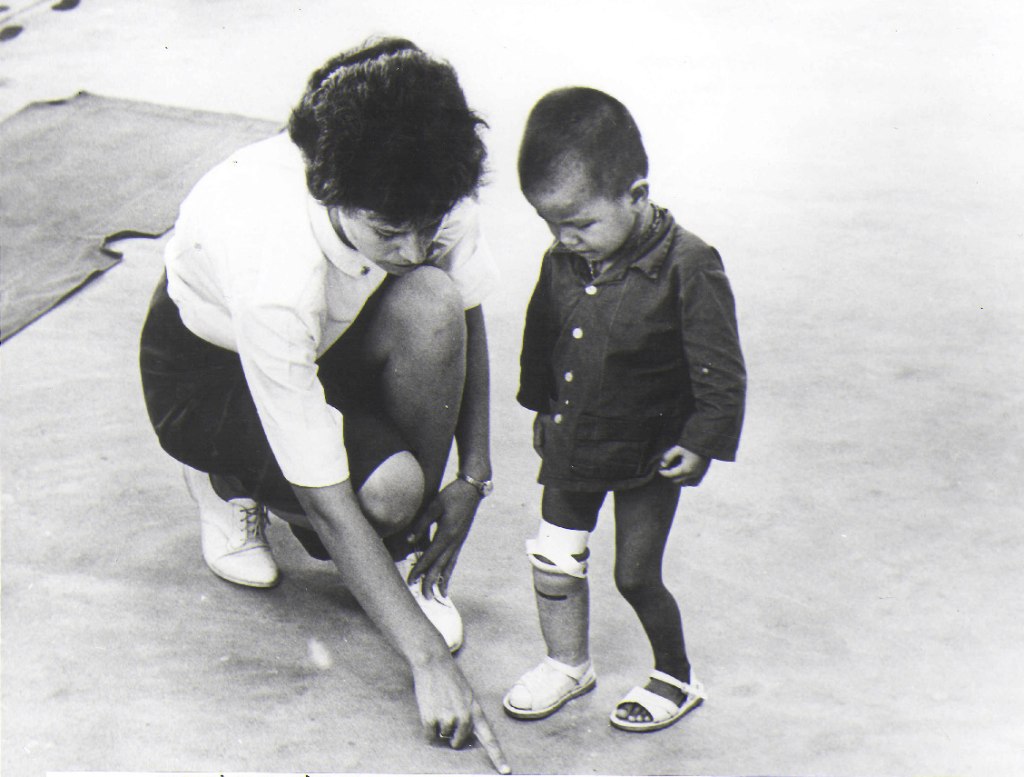

Through our research and communication project NARMIC (National Action/Research on the Military Industrial Complex), AFSC provided critical facts and analysis to help activists confront corporate war profiteers. After President Nixon announced the “end of war” in 1973, NARMIC and our staff on the ground in Vietnam revealed another story. Automated weapons were continuing to rain terror from the skies, not only in Vietnam, but also in Cambodia and Laos. From 1973-75, we campaigned and convened stakeholders to help bring a real end to hostilities.