Rosa Hernandez, at right, speaks at PVI’s Land Stewardship Story Circle. Photo: Eduardo Stanley

California’s Central Valley is one of the most productive agricultural regions in the country, providing over one-quarter of the food that feeds the U.S. population. Migrant workers have always been the backbone of the region’s agriculture industry. Over the years, they have included people from many backgrounds—from those who fled the Dust Bowl of Oklahoma and the Jim Crow policies of the South, to those from countries around the world in search of a better life.

For decades, immigrants and refugees in the Central Valley have also been building a small farming movement. African Americans and Japanese Americans were pioneers of small farming. Southeast Asian refugees who arrived in the Central Valley during the mid-’80s to mid-‘90s joined this small farmer movement. Mestizo and Indigenous Mexicans are now an integral part, as well.

While their backgrounds are diverse, the leaders in the small farming movement come from families and communities with close connections to the land. Their rich, Indigenous agricultural knowledge promotes biodiversity and land stewardship. That is especially crucial as the region—and the world—face the impacts of climate change.

Earlier this year, AFSC’s Pan Valley Institute (PVI) brought together 20 small-scale farmers, food entrepreneurs, and farm workers from the region for the "Sharing Land Stewardship Practices” story circle. The gathering is part of PVI’s mission to provide spaces where immigrants, refugees, and community members feel safe and welcome, learn from each other, and build a sense of belonging and power for social change.

During the story circle, participants shared their accomplishments and challenges in food production. And they explored how they could support each other, promote sustainable environmental practices, and work together toward food and climate justice.

Hear from four of the participants:

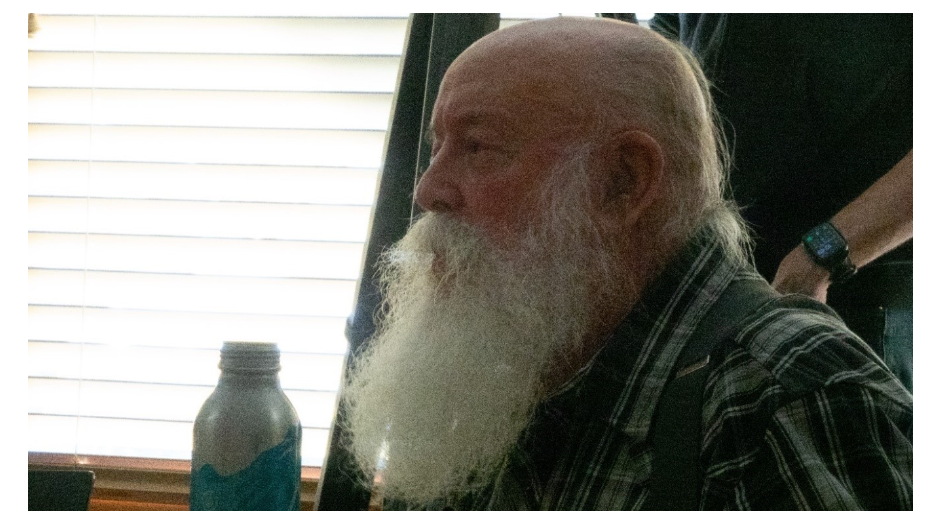

Tom Willey

Photo: Eduardo Stanley

Tom Willey has over 30 years of experience as an organic farmer. He and his wife, Denesse, operated T&D Willey Farms, a 75-acre organic farm in Madera, where they grew various Mediterranean vegetables year-round.

He opened the gathering and told the group: “If no other message comes out of this meeting today, telling your story authentically through whatever means that you move your product to the marketplace is extremely important. It's also extremely important that your product reflects your story.”

Paul Pearson

Photo: Fresno Foodways

Chef Paul Pearson runs a soul food restaurant in Fresno’s Chinatown. He opened PVI’s new cultural kitchen series, "Ancestral Culinary Knowledge: From Scratch.” The series goes beyond sharing traditional foods. It celebrates small food entrepreneurs dedicated to preserving traditions while fostering a profound connection to the land. This series will highlight the historical context and cultural significance behind each meal.

“I just saw something from Toni Morrison, who was my hero, my shero,” Paul said. “Morrison said, ‘If you are free, then use your freedom to free somebody else.’ And food is freedom.”

Rizpah Bellard

Photo: Nova Farming

Rizpah Bellard’s company, Nova Farming, educates youth and beginning farmers and ranchers—hoping to bridge the gap between humans and their food. Her work includes sharing the benefits of farming with people who have severe mental disabilities.

“They've really been pushed out of society because of their mental health, whether it's by drug use or trauma-induced schizophrenia,“ she says. “And here I am reconnecting them to their source of food, and they're helping other people get food. So the eggs that we raise, we donate them to families at the Central California Food Bank.”

Ia Yang

Photo: Eduardo Stanley

Ia Yang came to the U.S. via a refugee camp in Thailand. She recruited several relatives to pitch in money to buy 40 acres and then farm small plots. Her vegetables became so famous a book was written about them. But family is even more important.

“Having to farm is good, because my kids grow,” Ia says. “They have a lot of space to ride the bike or enjoy the land. I take them and our dog down to the field for good exercise. I teach them how vegetables grow. So they learn a lot about agriculture.”

Photo: Eduardo Stanley

Coming together to face challenges

During the story circle, participants recognized their shared challenges. The main one for small farmers is access to land—they rarely have the capital to buy it. Most have to lease the land, which doesn’t provide economic stability.

In the Central Valley—which is dominated by big ag companies—there is very little market for small farmers, let alone small organic growers. This forces farmers to travel hundreds of miles to Los Angeles or the Bay Area to sell their product.

Participants also recognized the need for small farmers and food production workers to support each other in overcoming their challenges. Now they’re exploring the possibility of developing a mutual support network to build a solidarity economy.

Our Pan Valley Institute team is honored to bring together small farmers, farmworkers, and food entrepreneurs for these vital discussions, helping them build trust and relationships. We’re excited by what we are doing together to create a more just, sustainable future for our region.