High school students in St. Louis conduct peer mediation to resolve conflicts among classmates. Joshua Saleem / AFSC

By using peer mediation and other restorative justice tools, Northwest Academy has drastically reduced student suspensions over the past few years.

While the fall temperatures have reached the St. Louis area, many of the trees are holding on to their green leaves. And although the weather is in transition, students and teachers at Northwest Academy of Law, a public magnet school in north St. Louis city, have largely settled into the routine of things.

Their normal routine, however, isn’t like that of other schools in the district. They are doing things differently with their nearly 350 students, almost all of which are African American.

Back in August, I was invited to present on the school-to-prison pipeline during teacher orientation week. The pipeline is alive and well in Missouri and St. Louis, with the Civil Rights Project at UCLA reporting in 2015 that “the state of Missouri now ranks No. 1 in the nation for having the largest gap in the way its elementary schools suspend Black students compared to white students and fourth in the nation at the secondary level. Statewide, elementary schools in Missouri suspended 14.4 percent of their Black students at least once in 2011-2012 compared to 1.8 percent of white students.”

In the presentation at Northwest Academy, I talked about the key driving factors that are pushing students, particularly students of color, out of school and into the criminal justice system. I talked about implicit bias—unconscious stereotypes that affect teachers’ expectations of students and how they treat them. And how schools often rely too much on harsh disciplinary measures, such as suspension and expulsion, that take students out of the learning environment.

Why would a school want to begin the year talking about policies and practices that push students down a pipeline toward incarceration?

“It’s important for our staff to be honest about what our kids are facing if we don’t do things differently as a school,” says Northwest Principal Valerie Carter-Thomas. “More than dismantling the [entire] school to prison pipeline, as a school our energy is spent making sure we’re not fueling it with our kids.”

After the presentation, Mrs. Carter-Thomas had teachers ask themselves what they were preparing their students for. If the school-to-prison pipeline is really at work, what alternative path do we want to create for our youth?

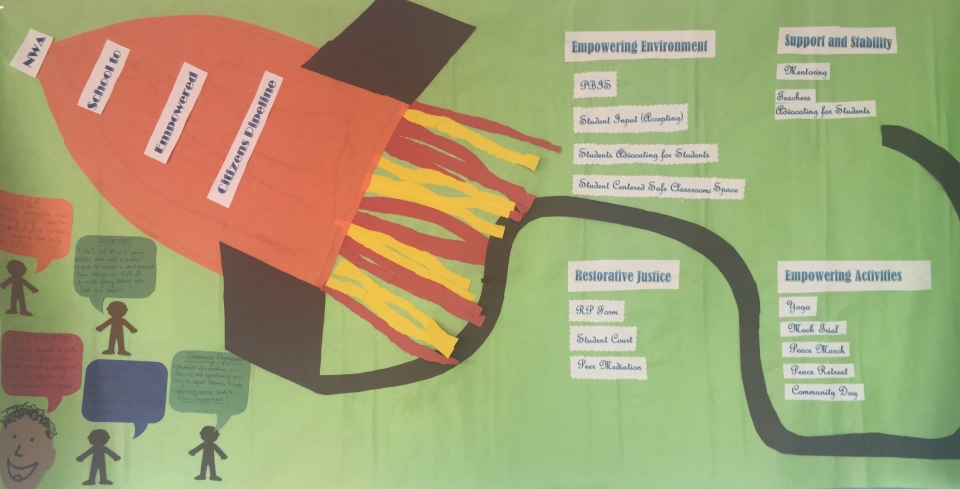

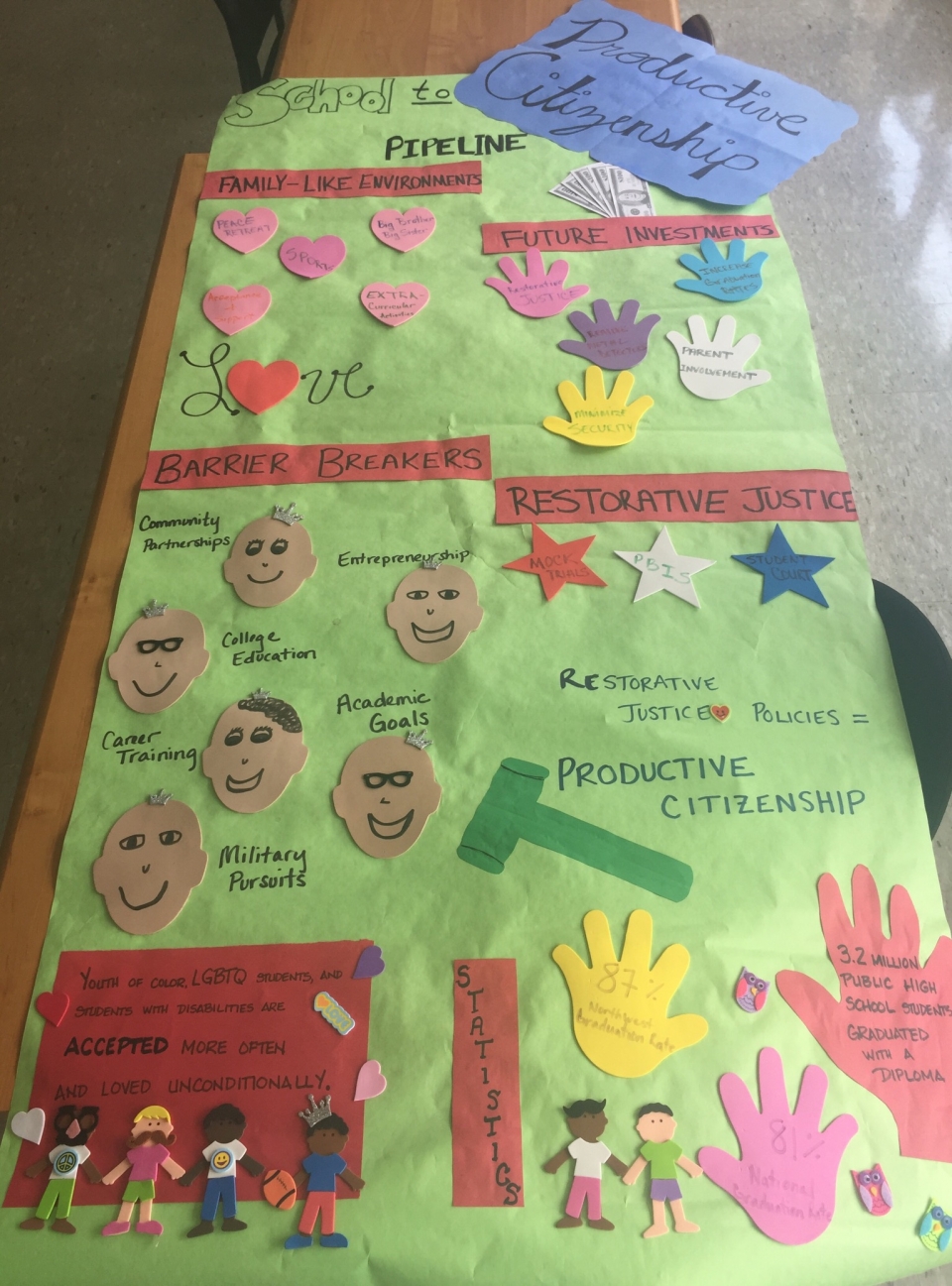

Teachers’ responses included the school-to-empowered citizens pipeline, school-to-community development pipeline, and the school-to-opportunities pipeline.

Creating an alternative pipeline

Over the past few years, Northwest Academy has developed several tools to keep kids in school and make sure they are on one of these alternative pipelines. Instead of suspending students for behaviors and offenses—as is common in other schools--students, teachers, and administrators can resolve conflicts through such tools as peer mediation, restorative student court, and restoration rooms.

In the 2013-2014 school year, for example, AFSC worked with students to establish the “Peace Squad,” a group of seniors who help other students resolve conflicts without violence. Using a mix of a secondary schools mediation curriculum provided by a local Quaker and AFSC’s Help Increase the Peace Project curriculum, these students have been successfully mediating conflicts for the past few years.

Recently, for example, the school’s social worker referred a student for mediation. There was a freshman who was looking for a safe space to discuss some difficult topics between her and some other students.

“I can’t wait until I can transfer out of this school,” the freshman said when she was brought to AFSC’s office, which is housed in an unused classroom in the school.

In the course of our conversation, it became clear that there was some bullying going on and this student was looking for a way to address it. In this case, we were helping to prevent conflict from escalating. In other cases, peer mediation has been used to address conflict that has already escalated, usually into a fight.

Instead of simply suspending students who have been in fights, the assistant principal who handles discipline issues refers students to mediation once things have cooled off. There they can get to the bottom of what caused the fight in the first place so that it doesn’t happen again. Had the feuding students been suspended, it would have been amounted to figuratively sending them back to their corners until they returned to school to rekindle the conflict.

According to Mrs. Carter-Thomas, “Suspensions say you’re not valued here. Just go away. It’s something else to say we need to fix this relationship. You are too important for us to just ignore this relationship.”

In addition to peer mediation, Northwest has also created “restoration rooms.” The brainchild of Assistant Principal Josh Henning, restoration rooms provide the space for students having trouble in the school day to be seen and heard one-on-one by an adult in the building. Instead of sending students having problems to the principal’s office or calling a security officer, a teacher can send the student to another teacher on their planning period to have a dialogue about what’s going on, and ideally, send that student back to class, ready to engage.

Seeing results

Earlier this month, I met with Mrs. Carter-Thomas during school lunch period to talk about the impact that these alternatives to disciplinary measures have had at Northwest Academy. And the results are significant.

Earlier this month, I met with Mrs. Carter-Thomas during school lunch period to talk about the impact that these alternatives to disciplinary measures have had at Northwest Academy. And the results are significant.

When the peer mediation program began during the 2013-14 school year, there were 107 total suspensions at Northwest. During the 2014-15 school year, mediation was in operation the entire year, and there were only 38 school suspensions—a third of the previous year's total. Currently, at this point in the 2016-17 school year, there have been only 10 suspensions, with the first semester almost completed.

AFSC has played a major role at the school, Mrs. Carter-Thomas tells me. "It is rare that you have an organization whose sole purpose is to teach people how to love each other," she says. "I think that’s paramount in what you do. It’s at the core of everything [AFSC] brings to us. For me it is a lightning rod, a focus, and a reminder of what is so important."

The three-second tone interrupted our conversation signaling that lunch was over. The freshman student who had requested mediation was to go to her last class of the day. A class she shared with two of the students with whom she had a conflict.

While the peer mediators were able to talk to two of the students involved and bring them to an agreement (they agreed to keep their distance from each other), two other students involved were absent that day so the mediation wasn’t complete.

Just as their process for resolving conflict was left incomplete that day, there is still much work to do in the school’s process of shifting from a punitive to a restorative discipline model. It isn’t easy, but as sure as the leaves will change colors and fall, so must the old and harmful way of addressing students’ behavior.