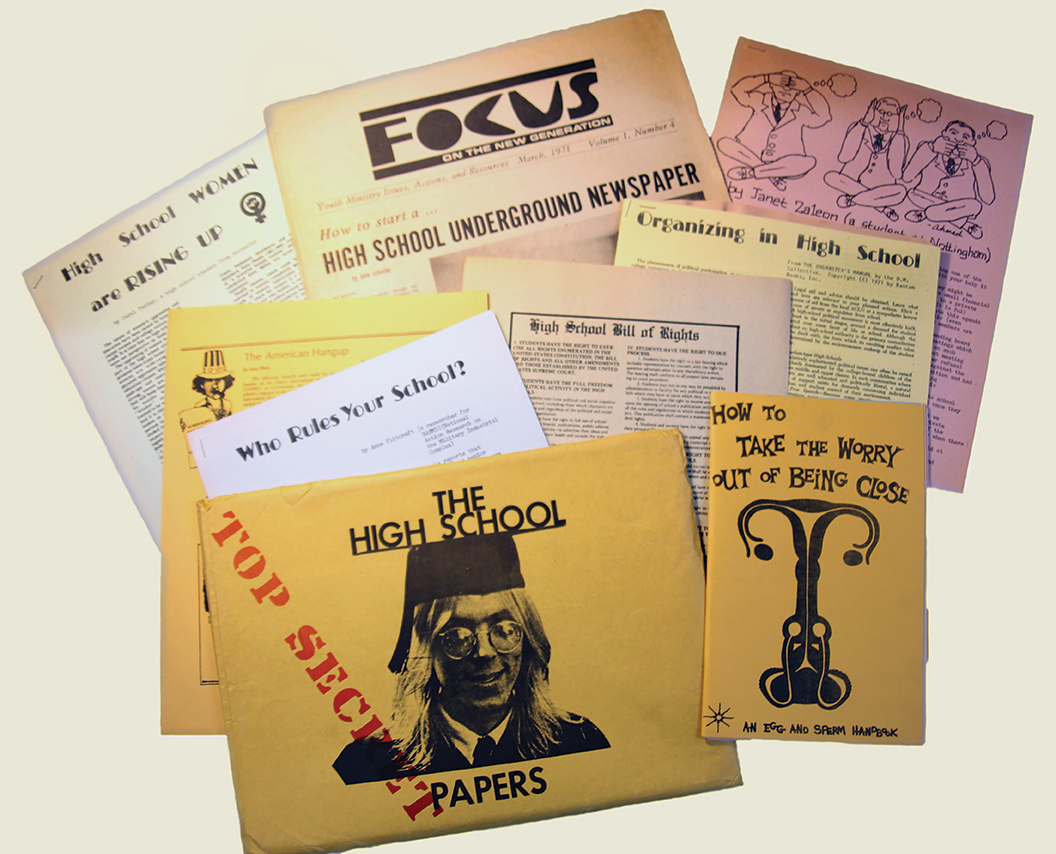

The collection of the AFSC Archives includes photos, artwork, films, correspondence, reports, personal journals, oral histories, publications, objects, and more. Nathaniel Doubleday / AFSC

What can we learn from history in a time of crisis? Thinking critically about our history can help us a great deal in difficult times. Our present is the product of people’s active choices, made in particular contexts under specific conditions in the past. Different choices might have produced different outcomes. We can uncover and illuminate such moments of opportunity in the past; our choices now can produce new paths.

In trying to make sense of how events unfolded in the past, we can recognize our own agency today to make things better. The archives of the American Friends Service Committee are filled with stories of ordinary people in challenging circumstances acting with extraordinary love to build stronger communities. Here are just a few examples:

Reason #1: AFSC helped resist Japanese-American internment

Building on decades of nativist and anti-Asian policies, the U.S. government seized on a moment of fear during World War II, and under the auspices of wartime national security, it forced 120,000 people of Japanese descent into incarceration camps. People’s lives were upended, their business and homes lost. How did people resist this racist inhumane policy, and what did they do to try to make the situation better?

In addition to many stories of active resistance among Japanese-Americans themselves, AFSC staff worked to challenge internment. They stood by their friends and neighbors, and they monitored and reported on conditions in the detention camps. Their work provided documentation for important court cases. And they worked to enroll Japanese-American students in colleges to secure their freedom. In the AFSC archives, you can find photographs, firsthand accounts, letters, published pamphlets, and oral histories that provide not only critical information about the brutal treatment of Japanese-Americans during the war, but shed light on ways that they and others resisted inhumane and racist incarceration in a time of heightened fear.

Reason #2: AFSC provided aid and training to out of work coal miners - in the 1930s

After World War I and into the Depression, the nation’s coal industry was in decline and communities that had relied upon coal mining were on the brink of starvation. Recognizing that coal’s demise was creating a humanitarian crisis, AFSC undertook relief work in Appalachian communities, likening the situation at home to what they had seen when they had done relief work in post-WWI Germany.

Beyond providing immediate relief, AFSC recognized that many of the people they served would never again make a living from coal. What would the future of coal country look like without coal? AFSC undertook a series of experiments in the 1930s, working with communities to try out different ways of adapting to a future without coal. It helped establish education and job retraining programs, a craftsmen cooperative, cooperative farms, and other programs that answered the immediate and long-term needs of coal country.

Check out the archives to learn more about conditions in coal country in the 1930s, to see photographs, video, and audio records from the era, and to see how AFSC organizers worked to restore dignity and economic justice to the communities they worked in. Read about a project that involved training unemployed miners to build furniture as part of the Mountaineer’s Craftsmen Cooperative Association. You can still see pieces of the group’s furniture in AFSC's central office in Philadelphia, where the archives are located.

Reason #3: AFSC supported sanctuary for refugees

In the 1980s, nearly one million people fled political violence in Central America and came to the United States seeking asylum. Official policy made it almost impossible for victims of right-wing regimes (that benefited from U.S. support) to gain protection in the U.S. despite the recent passage of the Refugee Act of 1980 establishing a right to asylum. Coming to the United States was dangerous, and many people perished in the desert after crossing the border. Others were detained and deported back to countries where they faced abuse, torture, and death.

Moved by the plight of these individuals and the injustice of U.S. policies, individuals and congregations began providing food, shelter, and haven for those seeking asylum. They came from different faith and activist backgrounds and became known as the Sanctuary Movement. AFSC supported the Sanctuary Movement by continuing work to provide legal aid, health care access, and other resources to refugees themselves, as well as by providing support and information to groups and congregations that offered sanctuary. As one of the movement’s founders Friend Jim Corbett observed, “Individuals can resist injustice, but only in community can we do justice.”

Even as the Reagan administration cracked down on the Sanctuary Movement, arresting and indicting several individuals for offering sanctuary, the decentralized movement kept up its work. In AFSC's archives, you can read a 1985 resource guide prepared by AFSC for Friends, a letter AFSC wrote to the president, and the response from the Department of Justice affirming the administration’s position that providing sanctuary broke laws. A lawsuit brought by a coalition of Sanctuary Movement member organizations eventually reached a settlement that provided many of the refugees denied asylum a new chance to apply.

We are made by history

These examples from the past have clear resonance today, as President Trump supporters defend the administration’s Muslim ban by invoking Japanese internment as precedent, as the plight of the dwindling coal industry and its workers continues to shape national discussions about meaningful work and wages, and as AFSC and others work to create sanctuary everywhere today to keep immigrants and others safe.

These moments resonate because they helped make the present we find ourselves in today. Nativism and racism, economic distress, and immigration restriction and deportations are not new problems, but deeply rooted ones.

Our history may not offer exact parallels or simple lessons, but by holding up the stories and examples of people resisting oppression and building inclusive communities in the past, we can draw inspiration from their example – and cultivate hope for the future.

For more information on visiting AFSC's archives, click here and contact us at archives@afsc.org.