Jennifer Bing / AFSC

AFSC staff recently spoke with Zeina Ashrawi Hutchison and Shaina Low, activists for Palestinian human rights. In a related article, they talk about their involvement in the No Way to Treat a Child campaign. Below, they share a few personal stories that motivate them in this work.

The memory of the beaten and hungry people on the mattresses has always stayed with Zeina.

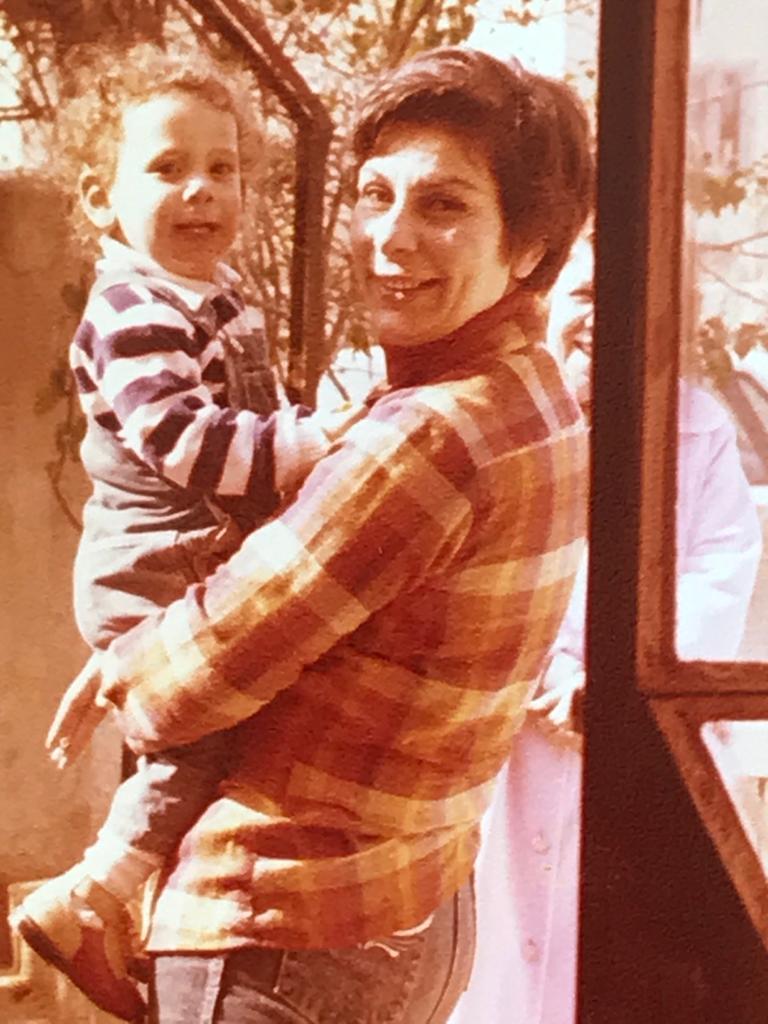

The daughter of Hanan Ashrawi, a leading human rights activist and feminist, Zeina grew up in Ramallah in the West Bank. “My mom would go to the Israeli military prison across the street and help save young Palestinian children from being imprisoned there,” Zeina recalls. “They were let out of the prison at all hours of the night, and we were the first house. Our doors were open, and we’d wake up in the morning sometimes and there were mattresses all over the floor with young men, beaten and hungry, sleeping in our house because they had nowhere else to go.”

The brutal reality of the Israeli occupation affected her every day. It wasn’t a long walk from her home to Ramallah Friends School, Zeina says. “But it was a walk in the real world: real sound bombs and teargas, real rubber-coated metal bullets and live ammunition, real pained cries and chants for freedom, and real fear. But It was also a cherished walk with my friends and my sister, a similar walk to the one my mother, her sisters and friends took to the same school, as children in Ramallah.”

Later, Zeina attended Westtown Friends School, Davidson College, and George Mason University. At GMU, she helped start a Students for Justice in Palestine chapter with a group of friends and was a leader in the Arab American Students Association. “One of the reasons I transferred from Davidson was because I needed to be around a larger Palestinian/Arab community,” she recalls. “I was in my late teens, suffering from culture shock and homesickness. I felt like I was carrying the stories of the people back home in Palestine as an amaneh, an invaluable treasure, that I needed to deliver.”

She describes her first class at GMU, Introduction to Middle East Studies, held in a massive auditorium. “I waited till the professor ended his presentation and asked if there were any questions. I raised my hand and said, ‘My name is Zeina, I am Palestinian, and I would like to start a Palestine group on campus. If you're interested in helping, please reach out.’ I was shaking and terrified, I didn't know anyone in the class or at the university, and I had no grand plan—I just knew I needed to deliver the amaneh. That day, I met two of my closest friends in college, Hanan and Lina, and we went on to organize together. We are still friends to this day.”

A different path to human rights work

Shaina grew up in Lincoln, Massachusetts, a long way from Palestine. Although she attended Hebrew school, her father and a childhood friend from Palestine helped her learn about the injustice of the Israeli occupation at an early age.

She recalls a mock peace summit in her 8th grade social studies class. When the teacher assigned all the Jewish students to portray Israeli officials, she strongly objected. “I got super angry and said, ‘I don’t want to be these people, I’m not these people, and I don’t like them.’ And my teacher said, ‘Maybe if you don’t like them, it would be good to learn about their experience.’ And I said, ‘No, I learn about their experience in my religious education,’ and so he made me Yasser Arafat, instead.”

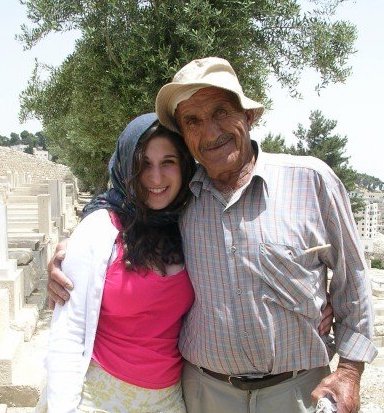

When she later travelled with her father to visit family gravesites at the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, they met an elderly Palestinian man, Abed Sayd, whose family had cared for the cemetery for generations. “He had this incredible memory and spoke a bunch of different languages,” she recalls. “He knew exactly where the grave was and, not only that, he remembered these relatives of ours who had buried my uncle there decades ago.”

Shaina says the old man was very sweet. “He cleaned up the grave, which had been covered in moss. We’re looking out at this beautiful view, and he casually points out the Separation Wall. My father asked him, ‘Has this impacted you?’ And he said, ‘Yes, I live on the other side of the Wall. It used to take me 15 minutes to get to work, but now it takes me hours. I’m worried about my children’s future. My children don’t want to stay in Palestine.’”

“All we could do was say we’re sorry,” Shaina remembers. “It was so humbling and humiliating to see and hear this man describe being treated like an animal at checkpoints, forced to walk through cages and being dehumanized, when he literally had devoted his life to taking care of dead Jewish people.”

The next summer, Shaina secured an internship in Palestine and befriended a family with four sons. “The father had been tortured in Israeli prisons and beaten,” Shaina says. “As a result, he suffered a traumatic brain injury and was never the same. The youngest son was 11 at the time, and he showed us the bullet wound he’d gotten when he was shot from behind through his thigh in the middle of the Second Intifada, when he was trying to get medical supplies to bring back to injured people in his community.”

People opening up and sharing their stories helped them become not just friends but family to her. “When I got back to the US, I felt this incredible responsibility,” she says. “I’d been given these stories and felt that I had to do something about it.”

“Palestine never leaves you”

Zeina says that she and her husband took their children to their first protests in DC when they were still in strollers. “We have conversations with our sons about Palestine—the beauty, power and injustice—at every opportunity,” Zeina says. “We want them to feel the sincere bond with our home and ancestry and the magnificence and power of solidarity. But mostly, I tell them about the many animals I had befriended, trees I’d climbed, fruit and vegetables I’ve planted and snacked on, and the perfect consistency and color of Palestinian mud for making mud cookies and handprint masterpieces on stone and concrete.”

She concludes, “You can be away from Palestine, but Palestine never leaves you.”