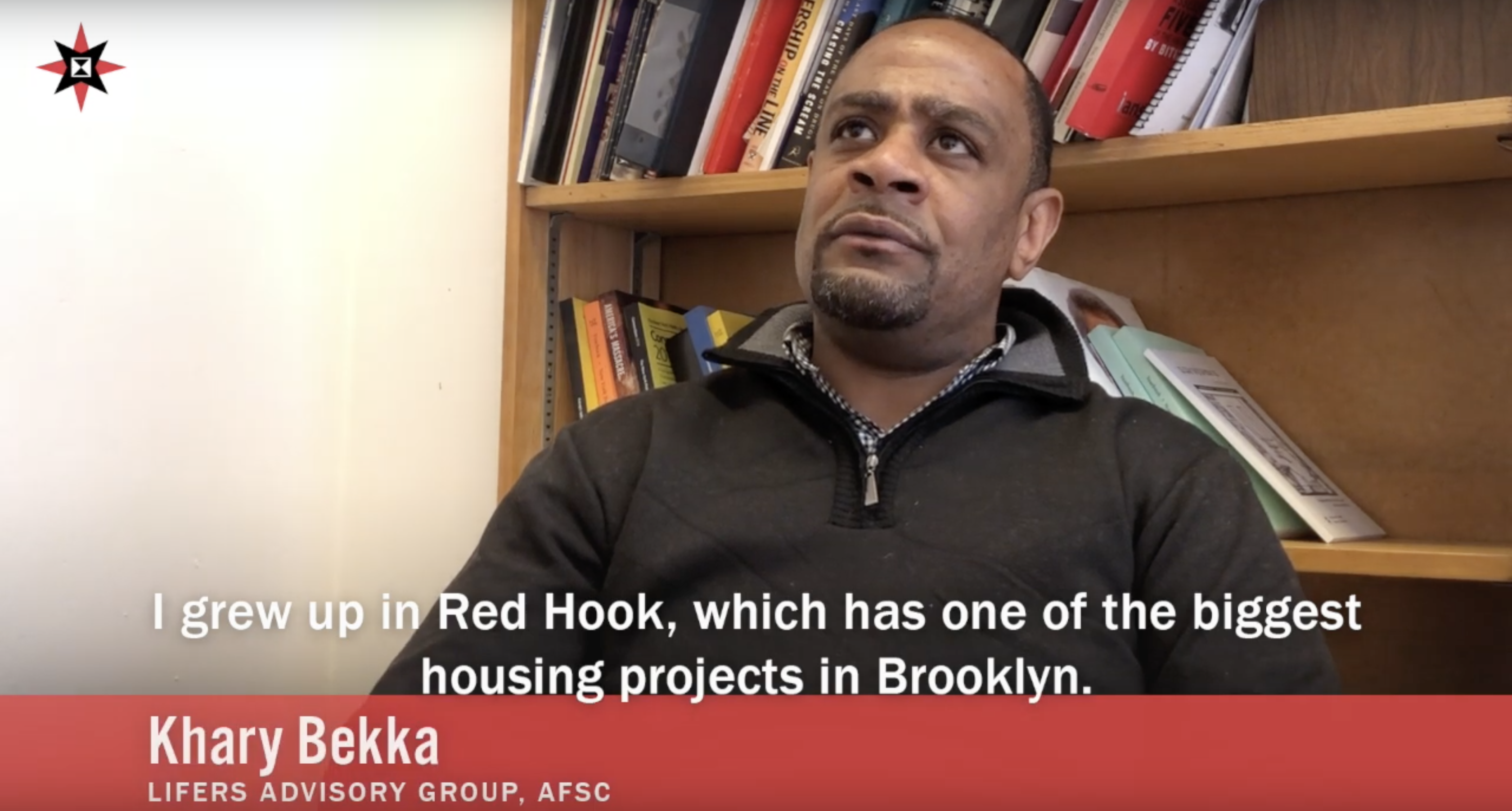

Khary Bekka is a native New Yorker from Red Hook, Brooklyn. He works for AFSC’s Healing Justice Program in New York City, which works with people affected by the criminal justice system. In 1993, Khary was sentenced to 25 years to life. He returned home in January 2019. He is an activist, storyteller, Quaker, and an advocate for restorative justice.

Sophia: What does being a Quaker mean to you?

Khary: Being a Quaker means being on the social front with a faith & practice that moves us towards championing social causes, that's an intricate part of Quaker history. So being a Quaker and having that direct relationship actually gives us a jump start in service while keeping a social relationship with God.

Sophia: How does your spiritual life relate to being incarcerated?

Khary: I only became a Quaker in 2012. It was interesting because I had done a lot of research on all different types of religions; I was searching for some form of truth. My truth took me back to the BC time, and I knew that meditation was a form of practice to establish a relationship with God. When I discovered Quakerism, I said, oh, this sounds familiar to me. I started reading, and I saw a core relation.

When we restructured the group and put in more silent worship I became a more humble person which I believe took me to the next level. I already had a spirit to serve, but silence really gave me the humility to take it to the next level. I think implementing a safer practice into my life really amplified that. That desire and that action to serve. I really value that inner connection, that inner light, the patience.

Sophia: Tell us your personal story with incarceration. What has it been like since you left prison?

Khary: The specifics behind my case -- we had gotten into a gun fight in the projects, and an innocent man got caught in the crossfire. I was young at the time, 18 years old. When I went to jail, I was still caught up in the mind frame of, it wasn’t my bullet that actually killed them. I was frustrated because I was sentenced to 25 to life, which left me questioning God, and asking do I really deserve this God?

The first 10 years was a real struggle for me. It was a struggle for me mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. And that inner turmoil that that struggle conduced expressed itself with outer turmoil, so I found myself getting into trouble. I found myself all over the place. Then there were instances that took place that started redirecting my life.

A major step came in 2003 when I decided that I didn’t want to sell drugs in the penitentiary anymore. I didn’t want to hustle the penitentiary. Where I believe I took it to the next level, I’m closing this door in my life, a life that I’ve been living for most of my teenage years, and my adult life at that time. While closing that door, I was opening the door for new opportunities.

Sophia: What would you like people to know about your story, your experience, and the prison system?

Khary: I think that the work that we're doing with workshops on trauma is a major step because you have to help people heal first. My story is unique because I came to jail when I was 18 years old, I was young. The brain is not actually developed until you are 24 years old. Now they are implementing laws that separate the children out from adults, now the guidelines are different, even going to the parole board, they have to consider the age of conviction. But there’s nothing being done to actually show some type of relief for people who got sentenced at 17 or 18 years old, and they are doing 20, 40, 50 years in prison. There is no relief for them.

And for me, coming out and saying I took steps in prison that really changed my life to go through the rehabilitation process -- and I know some other individuals who did the same, came to prison when they were young and took steps to go through the rehabilitation process, but they still have to do all this time in jail. My heart really went out to them. That’s wrong, that’s an unjust issue. There has to be some time of relief. Now there are laws that protect underaged people, because the brain doesn’t fully develop until you are 24. We’ll do something to stop the bleeding now, but what happens to everybody else that already got sentenced and there’s no relief for?

When I came out of prison, that’s the first thing that I wanted to do. I want to be the voice for the kids who came to jail when they were young and took time to rehabilitate themselves in the penitentiary, that are still in prison with no sign of release. And as a Quaker, I understand the historical aspect, the penitentiary being started by the Quakers. People deserve a second chance. When you look at the great prison reformers -- Elizabeth Hooton, Thomas Eddy, Eliza Farnham, the list goes on and on. And I said wow, why aren’t we trying to reform prison in this day and age? I believe that this was an issue that the early Friends would have championed, and I believe that I have inherited this issue once I became a Quaker. It inspired me, and that’s where I’m really coming from.

Sophia: What does a fair justice system look like?

Khary: I like what they’re doing out with the community at the Justice Center in Red Hook, Brooklyn. I think it was important for the American Friends Service Committee to partner with the justice system because that model of justice, where everything is not prosecuted, it’s a form of restorative justice. I think that community engagement in itself is an alternative to the criminal justice system. When we invest more in communities, when we invest more in nurturing healthy communities, as an effect of that, it offsets the criminal justice system. I don’t want a criminal justice system to exist; I want healthy communities. If we work on helping and investing in communities, I don’t think we’ll have a criminal justice system.

Sophia: What are a few steps we should be taking to building a restorative justice system and a more equitable system?

Khary: I think we’re taking the steps. The civic engagement that I’m involved in with the youth is important. I think that’s a major step because the youth is the future. The youth is going to be on the frontline of any social reform. I think what we’re doing with workshops on trauma is a major step because you have to help people first. It’s a healing process -- hurt people hurt people. If you take one father out of the community, it has an effect on the ecosystem of the community. A child is traumatized. When you see hundreds and thousands of fathers being taking out of the community, it has a disastrous effect on the ecosystem. To restore the balance of an ecosystem, we have to set in place programs. We have to set in place resources that keep families together, keeps fathers in communities, keeps mothers in communities.