Quakers demonstrate against the Vietnam War. Archives / AFSC

This is the first in a three-part series from my conversation with Quaker activist, author, and educator George Lakey. The transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length. Click here for part 2, and here for part 3. This story is also part of the "Let Your Life Speak" 2017 feature. Read the other stories from the project here.

Emily McGrew (EM): How would you describe your connection to AFSC?

George Lakey (GL): I often call it my mother [laughter], both because it was the first place I ever volunteered for a service organization, and it was also where I met the person who became my wife, in an AFSC summer project. So it felt like home folks, in a way.

EM: What was the project you worked on?

GL: It was called Interns in Industry, which was a popular project for a while after World War II. It was intended to assist college students to find out what working class life was like by getting an assembly line job in the summer, and then living together and in the evening having meetings with union leaders and economists and various people who could talk about what's it like in that part of the universe, which a lot of college students wouldn't otherwise get much chance to see.

I was a working-class kid who was brought up around factory workers and had worked in factories myself, so for me, I didn't go to the project to find out what that was about. I went because it was a way I could earn some money for school and also be in a Service Committee project because I liked the Service Committee. We kept being visited in our project up in Lynn, Massachusetts, by people who had lived lives of dedication, including Henry Cadbury, chair of the AFSC, an awesome figure in his day as well as since. I got a lot of exposure that summer to people who were living that kind of life.

I had the enormous good luck of being brought up in a fundamentalist Christian household, where Jesus was at the center of religion. I got to pay a lot of attention to Jesus and his life, and definitely got the impression that Jesus was not into running for popularity contests. [laughter] He was my great exemplar, I wanted to be like Jesus. And so I thought, “What is it like to be Jesus? Oh, OK, they might put you on a donkey and sing Hosanna and put palm leaves in front of your donkey and be delighted with you, and on the other hand, they might kill you.” It's a pretty big range of possibilities when you walk that walk. And so that will be true for my life as well.

It took a while to really work around that when I was 13 or 14, coming to peace with it. It wasn't until I was 19 [and in the AFSC service project] that I realized, "Oh, that really isn't just an ’in principle’ way of approaching life, but George, the purpose of your particular life is to be a prophet, is to work for peace and justice. That huge lesson you learned from Jesus on life is less academic than it seemed to you earlier.” It seemed real to me earlier because you never know what's going to come up. But at age 19 to realize, wait a minute, I will be intentional in my life [and] do things which will sometimes be controversial, because that's what prophets do. It was a kind of dawning realization, and then one night I just stayed out all night on the beach—Lynn is on the ocean—drinking in that realization that that's what my life was to be about.

EM: What's the connection between spirit and action for you? Can you tell me a story about when that was really vivid for you?

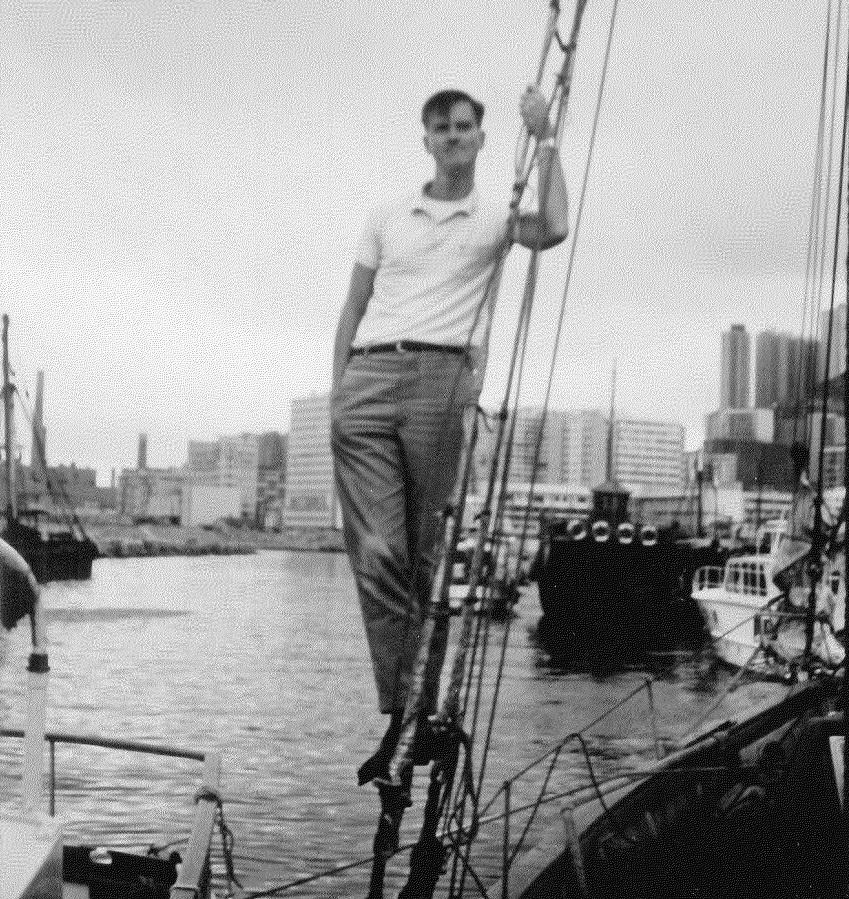

GL: I think the most vivid one was because it was life-threatening. I felt led to volunteer to participate in a sailing ship project during the Vietnam War, in which we were taking a sailing ship to Vietnam with medical supplies [for] civilians who were being hurt by the war. It was both a service project and an anti-war project, because it would be in defiance of what the U.S. [government] wanted people to do. Our plan had been to do three voyages, one to the North, one to the South, and then, to maintain the Quaker legacy of emphasizing the humanity of all peoples no matter the politics of their government, back to the North if necessary in order to get medical supplies to the third player in that multiple player, very complicated conflict. It meant sailing into a war zone. The first voyage was actually the most questionable one because we thought there was a reasonable chance that it would simply be disappeared on the high seas and nobody would ever know what happened to it. But it got through, amazingly enough, to North Vietnam and delivered the medicines and got back safely. Yay!

I was co-chair of the group, A Quaker Action Group (AQAG), and I was happy giving that kind of leadership, doing fundraising and that kind of thing. [I] hadn't any idea that I would want to volunteer. For one thing, I was so busy [being a co-chair], and also teaching and also being married and having a baby, and that was plenty, thank you. And then I was led, very... kind of clobbered over the head, with a leading that I should volunteer for the second voyage.

I felt like everyone else had a choice except me. AQAG could choose to send me or not because we had a committee who was stewarding all the many applications and deciding who should go to the next group. I felt like my wife could decide to divorce me or not [laughter], the meeting could decide to give me its blessing or not. It seemed like everybody had a choice except me. If way opened, it was very clearly my job to go. And way did open, and I did go.

EM: Can you tell me more about what that leading to go felt like?

GL: It felt like a real compulsion. I would've been relieved if AQAG had decided not to include me in the team, but also very disappointed because it really felt like it was God's intention that I go. Way opened, there was no question of my doing it, regardless of the fallout that might occur with regard to my job. As it was, the president of the place where I was teaching decided to fire me. I was financially insecure, my family was insecure...there were all these consequences, including the possibility that I wouldn't come back alive. And it was just clear as crystal, that was my thing to do, if AQAG decided to send me. As it turned out, the students where I was teaching ganged up on the president of the institution and forced him to back down and let me return to my job when I came back from Asia.

EM: What was the journey like?

GL: It was so multi-dimensional. I had never been on a sailboat before, so it was amazing that way, getting seasick and all of that. The crew was fabulous … the whole dimension of solidarity with an eight-person, international team.

The dimension of fear was very present, because we were confronted by a couple of gun boats and another boat, and then a U.S. patrol boat. There was a lot of weaponry around, and the weaponry tended to get charged in our general direction. Although obviously they could have hit us if they wanted to, we never knew if they would choose to want to. And we were very confrontational, we weren't just mildly withdrawing. We were very much hanging in there in the Vietnamese waters.

It was also hugely eye-opening for me. I was the diplomat of the crew, so before the actual voyage I went to Vietnam in order to negotiate arrangements with the parties. In Vietnam, I got to negotiate with the head of the Unified Buddhist Church, an awesome monk, who was kind of the Gandhi of South Vietnam. He had led several struggles, one of which had overthrown a dictatorship nonviolently. It felt like a miracle that I could actually meet such a person and be in his presence, even in a limited way. It was really one of the high points of my life, I would say. I didn't enjoy the fear, but fear is not there to be enjoyed, it's there to turn into excitement and then proceed as needed [laughter].