Note: This piece is one in a series of stories about spiritual journeys in prison, written by incarcerated people. Read more here and here.

For those who knew me as a teen, prison was definitely not a destination they saw in my future, and being confined in a correctional facility was unequivocally not in my plans. However, after some relatively significant trauma that left me unable to recognize how seriously troubled I had become, things turned bad…really bad.

Before turning twenty years old, I found myself charged with several horrendous crimes. After a long trial, I was convicted and sentenced to no less than sixty years in New Jersey State Prison. At that point, all of my aspirations became mere ephemeral romantic notions with no possibility of ever coming true. In addition, I had to resign myself to the fact that I would never again experience compassion, romance, or intimacy—feelings I treasured so much as a teen. Never in a million years would I find love again or be loved, not me, not in prison. At least that’s what I thought.

To fully understand how difficult a task it was to rediscover love, it is necessary to understand how I ended up condemned and isolated from society. The descending path I followed to prison led me, in a few short years, from being a promising, accomplished young man my parents were proud of, to being someone many people were ashamed to acknowledge.

When I was fifteen years old, one late spring morning, I walked to school with my friend Jay. He said he was very excited about taking Diane, his girlfriend, to the prom and almost equally excited about taking her in his father’s classic Corvette. That afternoon, Jay went onto a golf course with a shotgun, sat down on a picnic table, and blew his head off.

Jay’s suicide made absolutely no sense. He was smart, athletic, and seemed to be so happy—at least he was that morning. I’ll never forget telling Diane what had happened and sitting with her in the aftermath. After that day, every single time I ran into her, I could still see sorrow in her eyes. Jay’s suicide, and the memory of the anguish I saw, is something that is with me to this day.

Jay’s death was followed by a serious car accident. During a snow storm, four of us were returning from a football recruiting trip when I lost control of the car and crashed. Two of my best friends, Ray and Todd, died immediately and a third was injured. Since I was driving I felt responsible.

Even though I was released from the hospital, I was still devastated by the loss of my friends, and I did not want to be alive. Along with the emotional trauma, the head injury I sustained had changed me. My demeanor, disposition, and way of regarding the world had been altered. I was no longer the same person I was before the crash. I barely recognized myself.

I recovered quickly from a broken vertebra and ruptured spleen; but my behavior had been permanently effected. The long-term effect of traumatic brain injury isn’t something that can be picked up by a medical apparatus because what was lost was not physical or intellectual. Instead my temperament and the ability to govern my emotions had been severely diminished. I also lost the ability to relate to my own family, as if I did not belong with them or with anyone else. I even stopped feeling the same depth of love and connection to my girlfriend, Tanya. Feeling so “different” was disconcerting, but when I started having emotional swings way out of proportion to the circumstances, that made things worse. It was the first sign of troubles to come.

Back then, experts did not recognize how devastating head injuries could be. These days, science recognizes that the combination of physical and emotional trauma in a developing adolescent is a psychically toxic and potentially explosive combination. Much of the recent understanding is the result of war. Many veterans have sustained closed-head injuries; many suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, and most have survivor’s guilt. Although I never went to war, the physical and mental scars I experienced as a teenager were no less severe.

As soon as I was physically well enough, I returned to school intent on making up the assignments I had missed and graduating. In that month of my convalescence, my parents had decided to move to New Jersey to help my uncle and his family because his wife was dying from cancer. Even though my father pleaded with me to join them, I refused. Shortly thereafter, they moved away—promising they would not sell our house until after I graduated. Soon after, a “for sale” sign went up in the yard and people started to view our home.

My father would drive back on the weekends to check up on me and the house and Tanya would come over often, but most of the time I was alone. During this period, the situation at school started to deteriorate. Someone had started the rumor that I was drunk and that the accident was my fault, even though that was not true. I was ostracized by some and defended by others—and the conflicts that ensued began to tear the school apart. Then the mother of one of the boys who died in the car accident came over to the house and called me a murderer—she was screaming at me saying that I had killed her son and if she had a gun she would shoot me. Being blamed for the death of my friends was almost more than I could bear, but with the support and help from the few who stuck by my side, I struggled through.

Later that spring my father informed me that the house had been sold and that I’d have to move out before the end of the term. Even though I was having a hard time, it was still set in my mind to graduate. My father’s edict just added to the stress and my sense of isolation because I had no place to go. A few weeks later, my mother came back to town so she could pack up our belongings. Suffering from bipolar disorder and in the midst of a manic episode brought on by stress, she screamed at me that I had ruined their lives, and it was my fault they had to move away. I already felt abandoned and lied to, and with the way the kids at school had turned on me, the verbal assault by my deceased friend’s mother, and my mother blaming me for everything, the betrayal was complete. Less than five months after the accident at the age of seventeen, I could not have felt more alone.

The horrific crimes that followed took place more than two years after the car accident. I was nineteen years old at the time and two months removed from being released from a psychiatric facility. In that time I had refused counseling (despite my parents’ attempts to take me), had suffered another concussion (my third) while playing football for Fordham University, and had attempted suicide. While hospitalized after that attempt, I told the doctor that I tried to commit suicide because I could not control myself and was afraid I was going to hurt other people.

In October of 1988, I was charged with killing my uncle and his companion. I was convicted of those crimes and have been in prison ever since. The specific events leading up to that ghastly incident do not bear repeating. Because nothing is gained by reliving the details of that tragedy, I am conditioned to refrain from talking about the actual crimes. In addition, infamy has the potential to glorify deeds that should never be glorified. The people who died, member of my own family, did not deserve what happened to them. I am ashamed by it and wish it never happened.

During the first few decades of my incarceration, my emotions vacillated wildly from feeling sorry for myself and regretting the hurt I caused my family to intense bitterness or overwhelming guilt for all the pain I had caused. I often felt agitated or suicidal and looked forward to one thing—my own death. Sadness, more than anything else, was the prevailing emotion.

As I grew older, I became acutely aware that I was missing out on meaningful relationships. While life for me was stagnant, out in the real world, old friends and other family members were getting married, having children, and living their lives. A deep-seated part of me hungered to love and be loved, to matter to someone. I wanted to share whatever good, decent part of me that was left with a significant other. I was lonely and hurting deep inside, but for several reasons I could not do anything about it.

The first was fear. I had lost so many important people in the past I was afraid to open up. I also felt a mixture of shame and guilt, which crushed my self-esteem. Because of what had transpired in my life, before I could love anyone else I had to learn to love myself. That was going to be much more difficult.

Overcoming these feelings in prison was difficult or impossible; with few women around and no chance for romance or intimacy, it was easier to bury my loneliness deep down in my psyche. What I didn’t realize was that by suppressing my issues and not dealing with them, I was causing them to fester—and poisoning my existence.

Then, a few years ago, out of some administrative necessity, prison officials decided to establish a women’s unit right smack in the middle of a men’s maximum security prison. The women’s unit was secure and they were segregated from the men, but there were ways to see and communicate with them. When the women came into this facility, it caused quite a stir amongst the men; for me, their arrival marked the beginning of the healing process.

Just like I had never contemplated being incarcerated, neither did I expect prison to be the place where I would remember what it means to love. Behind the tall granite walls of the most notorious prison in New Jersey, I met a compassionate woman brave enough to get to know me, strong enough to help me, and smart enough to know how.

Mariea, an inmate facing her own sentence and her own problems, took on the arduous task of digging deep into my soul so she could help me figure out how to be at peace.

We got to know each other as friends first, with literally hundreds of people watching our every move. When the women went out to yard, I could see them from a narrow slot in the wall that served as a window. Their yard was at the base of the six stories of housing units filled with lonely men and Mairea’s long, gorgeous hair immediately drew attention to her. Somehow, her best friend noticed me and helped make our acquaintance. Not long after, Mariea and I agreed to start writing through the heavily monitored prison mail system.

A mutual attraction began to grow as we wrote back and forth, discussing our likes and dislikes, our pasts, our pains, and our greatest fears. Strangely, what we had in common, and what really seemed to pull us together, was our “baggage”. Despite the difficulty we had communicating privately, we quickly ascertained that we both harbored some serious issues that needed to be addressed.

Mariea had been the victim of domestic abuse, and I thought maybe I could help her work through some of her aversions. She thought she could help me overcome my suffering and finally realize some peace. Since we both wanted to try to work through our issues together, we embarked on a mutually beneficial course that ended up doing more for me than I ever thought possible.

Working within the rules of the institution, Mariea and I found ways to get closer. For example, we made up our own sign language to communicate when she went out to yard. I would wear socks on my hands so she could see me “sign” down to her from my window. Instead of writing about pop culture or gossip, we spent much of our time writing critiques about self-help books we both agreed to buy and read together. Or, we would fill pages and pages about the troubles we had that brought out the worst in us, sharing with each other what we did not dare share with anyone else. And, to make things even more personal, more intimate, we would also send each other poems, sketches, and photographs—things that came from our hearts; profound, meaningful tokens that cemented the promises and vows we made to never cause each other pain.

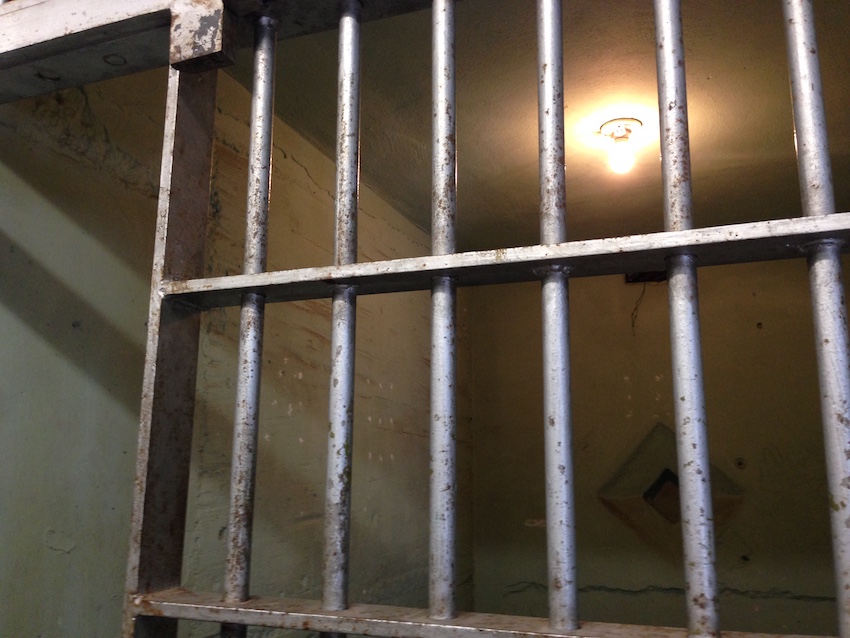

On a handful of occasions, for a few brief seconds, Mariea and I came face to face with nothing but a few steel bars between us. It only happened when an officer was escorting her to work in the moments after I was called out to school to tutor. Our paths would cross, and there were only fleeting glimpses; but in those moments, everything and everyone else disappeared—it was just us.

Mairea encouraged me to meditate and convinced me to take up yoga. Several stories apart, at the exact same time, we would practice and do asanas from routines she had developed. That was one way we could feel closer while still improving ourselves. She also encouraged me to enroll in correspondence courses to help me learn to love myself. Mariea signed up for the courses “with” me so we could do them together.

Mariea did a lot to help me, but the most important thing she did was to encourage me to take on the car accident to try to come to terms with the loss of my childhood friends. With her support, I finally worked up the nerve to go into counseling to deal with the post-traumatic stress disorder and survivor guilt that had burdened me for twenty-five years. Through all the tears and the heartache, she was there for me, writing to me and asking how things went after every session, telling me it was okay to let go, and never, ever making me feel weak or inadequate for letting my emotions flow.

No one has ever loved me so much or cared about me so deeply yet asked nothing in return. Although the things we did together required me to put forth plenty of my own effort, it was all made meaningful because Mariea loved me enough to care. Her effort proved to me that I was worth saving, worth loving—and she planted the seeds that got me on the path of learning to love myself.

In the time Mariea was here, we never touched—no matter how badly I wanted to hold her hand or hold her in my arms. We never kissed, no matter how often I prayed, entreating a Higher Power to give me that one precious moment to feel her lips pressed against mine. Even without physical contact, I fell deeply in love with that sweet lady because what we were able to share made me feel human.

Mariea doesn’t know it, but I am alive today because of her kindness, her patience, and her love. Since our time together, I no longer wake up screaming from dreams where I’m crashing a car and killing the people I love. Also, I can now sleep soundly at night without taking medication. She would never accept the credit for this but I believe these changes came about because she loved me and proved to me I was worth loving. Because of her I no longer hate myself.

Never in a million years could I have predicted that in a maximum-security prison I would fall head over heels in love with a beautiful, kind, spiritual woman who dared to love me despite my past and my flaws. Never in a million years could I have predicted that she would come into my life and convince me it was okay to forgive myself, that I should love myself, and then prove to me that I was worth loving. Never in a million years would I have guessed that I would once again be able to smile.

Unfortunately, what Mariea and I shared did not last, but what did endure was the metamorphosis; a transformation brought about by unconditional love, where, for the first time in a quarter century, my soul was at peace.