The Lotze plumbing business opened in California after the Lotzes came to the United States Courtesy Mike Merryman-Lotze / Mike Merryman-Lotze

My Great-grandpa Jarvis came over to the U.S. on his own from Greece when he was a young teenager. He didn’t want to go to school or stay in his small village, so he packed up and moved to the U.S. where some of his cousins lived. He eventually ended up in Portland and gradually moved from selling fruit out of a cart to owning a fruit and vegetable store.

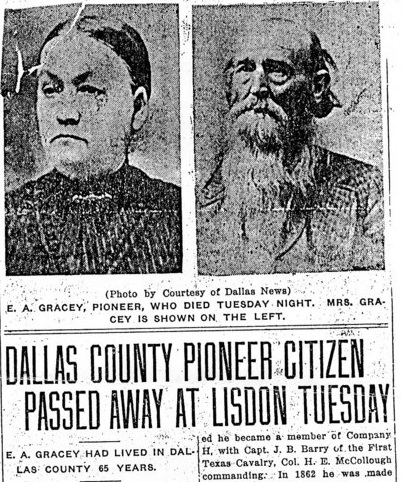

My Grandpa Lotze’s parents moved to the U.S. from Germany in the early part of the 1900s. They were Brethren pacifists and moved to keep their kids out of military service. They settled in L.A. where they opened a plumbing business that still exists today.

Then there is the Lackey side of the family. I don’t know very much about how that side of the family ended up in the U.S. Others know more, but the family (under other names) traces back much further. I do know that I had ancestors on that side of the family in South Carolina who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War.

There were also the Joneses. I’ve never met anyone from that side of the family, but there are rumors that the family traces back as far as the Mayflower. Keeping up with the Joneses? They were those kind of Joneses.

The Jonses were also in South Carolina and/or Texas during the Civil War and fought for the South. More than one of my ancestors on this side were early Texas Rangers. A write up about my Great-great-great grandfather Emory Augustus Gracey, who links to the Joneses five generations back, in an official Texas history includes this little gem:

“Next he joined a party of rangers, who were scouts and had several fights with the Indians. They killed one Indian, captured two, and recaptured nine horses at one time, and thirteen at another. After a year thus engaged the great Civil war broke out, and Mr. Gracey enlisted in Company H, Captain J. B. Barry, of the First Texas Cavalry, Colonel H. E. McCullough commanding. They took the first line of posts vacated by the United States forces on the frontier of Texas; next were at Camp Cooper, when that was surrendered to the Confederates, and remained there until April, 1862, ten months, during which time they were in eight engagements with Indians, killing seventeen of the red savages, and captured forty-seven head of horses, and losing four men killed and thirteen wounded, besides two mortally frightened, at least they were never heard from afterward.”

In terms of nice immigration stories, I’m limited to two for four.

Since I’m officially a Lotze it would be easy to pick the convenient stories and bury the other two. The Lotze story is recent and has personal meaning. It is a story about pacifists fleeing religious persecution and I can feel good about lifting it up for public viewing.

At recent protests one of the popular signs reads “We Are All Immigrants," and with that in mind I could hold up this personal immigration story as an example of why our country must remain a place of safe-haven for those seeking freedom and opportunity – something I fully believe.

But the truth is that we are not all immigrants and even those of us who are descended from immigrants don’t have simple histories. The comfortable story is incomplete.

We must recognize that:

Some of us are indigenous to this land and come from families scarred by genocide and forced displacement at the hands of immigrants and colonists.

Some of us are descendants of people brought here in chains as chattel slaves.

Some of us came to flee violence, poverty, and oppression.

And some of us are the descendants of immigrants, but immigrants who came here as settler-colonialists, displacing and killing the land’s indigenous community, while keeping others in chains as slaves.

Some of us still benefit from wealth and societal positions that have come down to us – both directly and indirectly - as a result of our ancestor’s oppression of others.

Most of us share multiple and complex histories.

And we don’t get to pick our stories and histories.

We need to be brutally honest about our history. We need to not only recognize the parts that make us feel good, but also the parts that make us uncomfortable or that perhaps engender shame.

For those of us who are white in particular, it is important to move beyond simple, happy narratives about immigration and gradual integration within a supposed melting pot society. We need to open and air our dirty history. If we don’t embrace and fully understand that dark history, then we will never be able to understand the present realities of others impacted by what is a shared history.

That in turn will continue to keep us from moving towards reconciliation, reparations, transformation, and justice.

Related Content

Schooled in disconnection: Waking up and struggling for racial justice

10 ways white supremacy wounds white people: A tale of mutuality