In September 2015, Pedro joined AFSC colleagues from around the country on a delegation to the Occupied Palestinian Territories to meet with farmers, business people, politicians, and activists, in order to learn about how Israeli occupation impacts daily life for Palestinians living in the occupied territories. The staff delegation visited the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and Jerusalem. This is one in a series of articles on Pedro’s reflections on his visit to Palestine. - Lucy

A Palestinian child, no more than 10 years old, stood in the middle of the street near the checkpoint leading to the entrance of the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron. In his hands he held a flute similar to those Palestinian merchants sell to the few tourists that make their way into the deserted streets of Ghost Town. The boy blew into it until he was almost out of breath, standing his ground, and blowing a second time with as much fervor.

My colleague Khadijah went to his side, resting her arm on his shoulder. Both stood fiercely in the middle of the street exposed to the dozens of children and young exuberant Israeli teenagers, flanked by armed chaperones that moments before arrived in large passenger buses with festive flare. They were a rambunctious group of settler youth; they could have been on a field trip from school, taking a break from their studies, I don’t know. But here they were blowing into shofars of different sizes, making offensive jeers and taunts meant to disrupt the prayer heard through the speakers on the tower of the Ibrahimi Mosque. As the young boy blew into his flute, contrasted against the menacing mob in front of him, each breath seemed to be an affirmation of self, of identify, of belonging. He was resisting the occupation.

Ten minutes before that, a white-haired bearded man in his 50s accosted members of my delegation by shoving and yelling at them. He was blowing into his shofar with all his might each time the call to prayer was broadcast from the nearby mosque. He was determined and crazed, yet, protected. Nearby Israeli border police stood guard at the double checkpoints that lead into the Ibrahimi Mosque where the tomb of Abraham is located, and where in 1994 an Israeli settler, a US citizen from Brooklyn, massacred 29 Muslim worshippers and wounded another 125 until he was subdued and beaten to death by those the bullets missed.

My colleague Dalit had approached the man with the shofar to ask him why he was disrupting the call to prayer, and he became belligerent and aggressive, pushing and yelling at her and swatting at another colleague, causing the border guards to intervene.

From the opposite side of the street, about two-dozen settler youth, also accompanied by Israeli civilians draped with automatic rifles, were raucously chanting and making their way in our direction. We could have been caught in-between, so our guide escorted us off to the side allowing the youth to pass. We took a final photo of the boy with the flute, this time with a friend who wasn’t much older next to him. They smiled and signaled peace signs with their hands. Behind them, the settler youth swelled in numbers and the noise they made became even more boisterous.

Our guide, Jawad, a member of Youth Against Settlements, shared with us that Hebron, the largest Palestinian city in the West Bank, was divided into two sectors after the 1993 Oslo Accords, where H1 (about 80% of Hebron) is under Palestinian Authority, while Israeli forces control H2 (about 20% of Hebron). The group Jawad is a part of is a non-partisan community group that uses non-violence and civil disobedience to call for an end to the building and expansion of unlawful Israeli settlements.

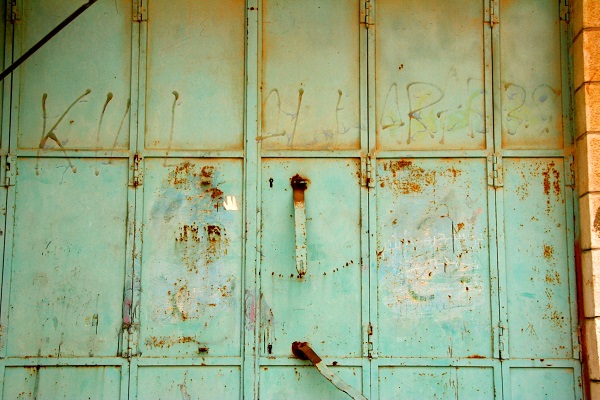

Before entering the Ibrahimi Mosque, Jawad led us through Al Shuhada Street, where most Palestinians shops remain indefinitely closed and where the remaining Palestinian families live under constant threat of reprisal. Once a bustling marketplace, the area was nicknamed Ghost Town because Israeli military officials forbade Palestinians from opening their shops after riots broke out in response to the massacre in 1994. For the Palestinians that remain, getting to their homes is highly restricted and controlled by a series of military checkpoints placed throughout the neighborhood. Palestinians also have to be cautious as heavily armed soldiers patrolling the streets and vigilante settlers often in collusion attack Palestinians in the area. The neighborhood here is now comprised of empty walkways with closed, rusted metal doors. Where an occasional shop is open, the business owners sit outside smoking cigarettes – there isn’t much traffic here.

The remaining shopkeepers have placed tarps and wire mesh to protect themselves from trash and rocks tossed at them from above, where settlers live. Looking into the sky, beyond the protected layer of mesh and wire, an armed guard in a military tower watches over us. This and numerous cameras placed throughout the walkways are meant to observe and calculate Palestinian movement.

In addition to forced evictions and restricted movement, Jawad shared that Palestinians must contend with curfews, vigilante settler violence, unlawful detentions, especially of minors, and are subjected to military law. Hebron under Israeli occupation means that collective punishment is the de facto rule of law.

In recent weeks, an escalation of violence in Hebron and throughout the Occupied Palestinian Territories has led to loss of life for both Palestinians and Israelis. The tension increased when Israeli forces raided Jerusalem’s al-Aqsa mosque in early September, injuring many Palestinians by firing tear gas and rubber bullets into the mosque, arguing it was a preventive measure against Palestinian protests at the eve of the Jewish holiday Rosh Hashanah. Palestinians across the Occupied Territories protested, compounding tension that was already explosive from an incident in July where Israeli settlers firebombed a Palestinian home in the West Bank, killing an 18-month old infant and his parents. The Red Crescent has declared a state of emergency in response to settler violence during the month of October.

In the past month near the checkpoint in Hebron where I crossed from H1 to H2, recent clashes between Palestinian youth and Israeli military have resulted in deaths. According to the International Middle East Media Center, an independent media outlet made up of local and international journalists, these are incidents that occurred on just one day, October 14:

- “Israeli forces shot a 17 year-old Palestinian in the chest in the town of Beit Awwa, west of Hebron

- A 13 year-old Palestinian boy was shot near his eye with a rubber-coated steel bullet

- Israeli forces fired tear gas canisters at locals, causing several to suffer excessive tear gas inhalation. They also detained a Palestinian after brutally assaulting him.

- Israeli forces also broke into several houses in the town, occupying and turning their roof tops into military watchtowers”

The Red Crescent also reported “that over 400 Palestinians were injured during clashes in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip” a day before, “where at least 31 of whom were shot with live fire,” with one fatality in Bethlehem.

Of my visit to the West Bank, Hebron seemed to be where I most experienced an intensified feeling of collective distress and frustration, as if people there live under a constant premonition that something horrible is about to happen.

Later that day at Jawad’s home, as we enjoyed a hearty home-cooked Palestinian meal, we discussed our encounter with the aggressive Israeli settler, we remarked about the presence of heavily armed military personnel at the checkpoints and along the streets, about the soldiers wearing battle helmets that abruptly closed the checkpoint preventing us from leaving H2. I thought about the 10 year-old Palestinian boy in the street, countering the cacophony of the obnoxious settler youth by taking a stand with a single flute. Of the madness of what military occupation has done to Hebron, I was able to discern that there is hope in his resistance, and like my colleague Khadijah, my place is to be by the boy’s side.

Related Content

Address root causes to end violence and bring justice in Israel and the Palestinian territories

Tragedy and transformation: Visuals of violence in Palestine