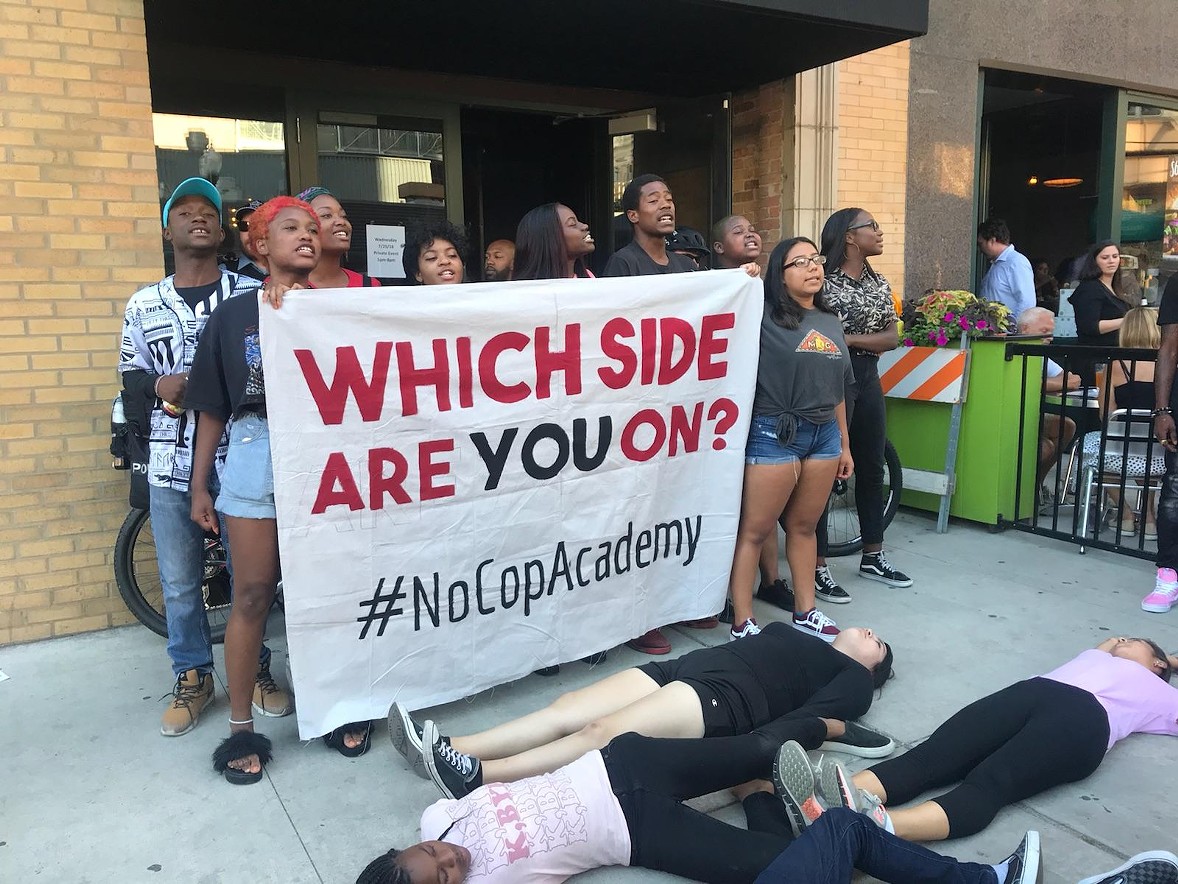

Youth blockading entrance to Black City Council Representatives’ fundraiser for #NoCopAcademy #NoCopAcademy

Debbie Southorn works for the American Friends Service Committee in Chicago, where she supports community efforts and youth organizing to end policing and reimagine community safety. In 2012, she co-founded the Chicago chapter of Black & Pink, currently serves on the National Committee of the War Resisters League, and is a Board Member of the Chicago Freedom School. She’s written about policing and white supremacy for outlets including Truthout, In These Times, and The Intercept. Read part one of her interview here

Sophia Perlmutter: What is your vision for an alternative and what’s a step in the right direction to end this oppression?

Debbie Southorn: I think that there’s a whole lot of work that needs to be done and it’s happening in important ways. A lot of this work has been led by incredible Black feminist organizers and abolitionists like Mariame Kaba or Rachel Herzing, formerly of Critical Resistance, that’s really trying to ask people critical questions about what we think police do. And we can’t talk about policing without talking about the larger criminal legal system. I think the current paradigm that we live under is this question of who did it and how can I punish them? And it doesn’t even always matter if we get the right person; the importance and the focus is on punishment and locking people up.

What would it look like if we reimagined a justice system that instead asked us who was harmed, what do they need in order to heal, and how can we make sure it never happens again? A lot of this work is being done by folks in restorative and transformative justice circles, I think there’s also so much work to be done around just rebuilding a strong social safety net and having real access to community resources and services in Black communities, in marginalized communities all over the place, but especially in Chicago where we’ve seen a real apartheid of resources.

In the north side you can walk a few blocks and find the services that you need but it’s very rare to find these services on the south, far south, and west sides of the city. Instead what we’re seeing is the expanding role of the police.

Chicago closed down half of its mental health clinics in 2012 to save the city $3 million and now instead of opening new health clinics, we’re providing more mental health training to the Chicago police, and having more crisis intervention teams within the Chicago police department. That doesn’t get at the root of how we support people dealing with mental illness and how we demilitarize responses to mental health crisis. Instead it just further exacerbates the possibilities of people in mental health crisis coming into contact with law enforcement and potentially seeing the end of their life, like what happened with Quintonio Legrier in December of 2015 or Michelle Robey, who was a white woman killed on the Northwest side a couple of years ago during a mental health crisis.

Again, it’s about reimagining what we even think a criminal legal system should do. We have to figure out how to constantly be working to defund, demilitarize, and dismantle the current institutions of policing and incarceration. Every penny that we spend on CPD is a penny not spent on an afterschool program or a textbook or health care or a counselor in a school.

In Chicago, we spend $4 million a day on the police and that’s not including misconduct settlements, or overtime, and that’s not including the new $95 million cop academy. This adds up to be about 40 percent of the cities operating budget. We spend more in one day on policing than we do over a year and a half on violence protection in the city. So it’s really about changing and transforming our priorities and rebuilding our political power that forces our elected officials to get on board with the reimaging and the reprioritizing of Chicago.

Sophia: What is your hope for the city of Chicago? What would you like Chicago to do in place of the police academy?

Debbie: I want Chicago to be just. I would love Chicago to reckon with its incredibly racist and violent past and current realities in terms of the ways that it administers who gets to live and who doesn’t through the various social and economic systems. I think I want to stay away from prescribing what I want to see instead because it feels important that that be driven by young Black folks within the #NoCopAcademy campaign, residents of West Garfield Park, where the cop academy is being proposed to be built, students at Orr High School, etc. We know that one new afterschool center or one new community center isn’t going to do what’s needed in terms of ending violence in the city. Instead, stopping the cop academy would be an important first step on the way towards acknowledging the skewed priorities and shifting spending in the city. There isn’t one simple thing that we want instead. There are so many.

For example, there were community activists trying to open a school in that neighborhood less than a mile from the cop academy 10 years ago, that couldn’t get the TIF (Tax Increment Finance) money used for a school. But because the mayor controls this money, that land was purchased and that money was used for a cop academy against community desires. We have money, we have resources, we just don’t have the political will in office to shift resources to the community. This campaign is trying to say, the people want these resources, we’re going to be loud, we’re going to be in your face, we’re not going to go away, until there is the political will to do things in this city in a different way.

Sophia: How do you integrate nonviolent direct action into your advocacy and as you’re working on stopping the cop academy? What’s working and what isn’t working?

Debbie: I think from the get go it’s really important to acknowledge that a big part of why this campaign has had any success at all, much less had some wins along the way, is that it’s been really led and directed by young Black folks and folks of Color who are teenagers that are tired of the way that this city has been ignoring them. From the onset of when we started envisioning and planning this campaign there were Black teens at the table helping to strategize and almost all of the direct action that we’ve carried out has been driven by that core of young Black folks.

I encourage people to check out the “No Cop Academy” report because that’s where we really lay out our strategy for this campaign. We talk about disruptive power. We don’t actually use the words “nonviolent direct action” that much and I think some of that is on purpose recognizing that nonviolence can get weaponized as a phrase to discredit acts of rebellion that are nonviolent, but that are seen as violent because they maybe don’t prescribe to a white middle-class lens of nonviolence.

There are ways that that language hasn’t been particularly used or centered within our work but is super connected to these ideas of disruptive power. If you understand power at its core as the ability to make things happen, then it becomes possible to disrupt business as usual when we are directly challenging the power structure, when we’re disrupting the power structure’s ability to make things happen the way that they usually do.

You can try to go through the methods that they give us, and we’ve filed several lawsuits against the city because they don’t follow their own rules. But we can’t rely on the formal channels to give us what we want.

One fun type of action has been trolling the mayor. We had people on six different college campuses across the country interrupt his speeches when he was doing a speaking tour earlier this year. We’ve confronted him at lunch, confronted him at an Iftar dinner during Ramadan. We are coming out of the woodworks to say to him, “You’re not safe anywhere you go until young Black folks in this city are safe.”

Sophia: What does a just world look like for you?

Sometimes I just like to dream big, that with white folks across the U.S, there would be a huge reckoning with white supremacy, and we would see millions of white people throwing down for racial justice and we’d see a complete redistribution of resources that Black people in this country have been demanding for centuries. A just world means we’d see people in their communities able to make decisions about the things that affect their lives, that there wouldn’t be people in cages, that when people experience harm, that they would actually be able to get the support that they need.

I would dream that the distinct and powerful histories of liberation movements, indigenous movements, Puerto Rican movements would be honored and celebrated. I keep thinking that there would have to be some intense reckoning of the violence and destruction that we as white folks have carried out for the last 500 years, there would have to be different way of doing things, so that people would have access to what they need to live, and that violence would be seen as tragic and not common place.

I also think it’s more important that we look towards the visions that are coming out of these movements for liberation as we’re setting our course towards a more just society and a more just world, that we actually have lots of models to look to, such as the ways that queer people of color are really trying to build out community accountability systems that don’t rely on policing and prisons.

There’s little scrapes and visions and cracks in the way things are right now and what we need to do is hone in on those and expand them. Even though things seem overwhelming, that means it’s probably even more possible right now for us to win some radical transformation.