Last July, my six housemates and I finally finished hauling all our furniture off the enormous moving truck and sat down in the cross-breeze of two fans to hash out who lived in what room in our rented Victorian rowhouse in West Philadelphia.

Each person laid out their ideal room criteria—I wanted a room on the third floor to be isolated from most of the noise from downstairs, Richie wanted a room big enough to put a couch in, Gage wanted to beat the rising summer heat by living on the second floor, Barbara and Lena wanted lots of natural light so they could grow plants. We figured out what to call each room (third floor funny shaped, second floor front, carpeted middle one) and took another lap around the house to eyeball them down.

We started with a sort of straw poll. Everyone laid out their top couple choices, on the off chance that we had all chosen differently. Unfortunately, most everyone landed on the same three spacious end rooms with hardwood floors and lots of windows. Bummer.

So we refilled our water glasses and settled in for a longer conversation. We don’t all have the same definition of Spirit, but we certainly do a sense-of-the-meeting business process. We weren’t going anywhere until we had all arrived at an agreement without resentment, reservations, or coercion.

There’s a graph for that

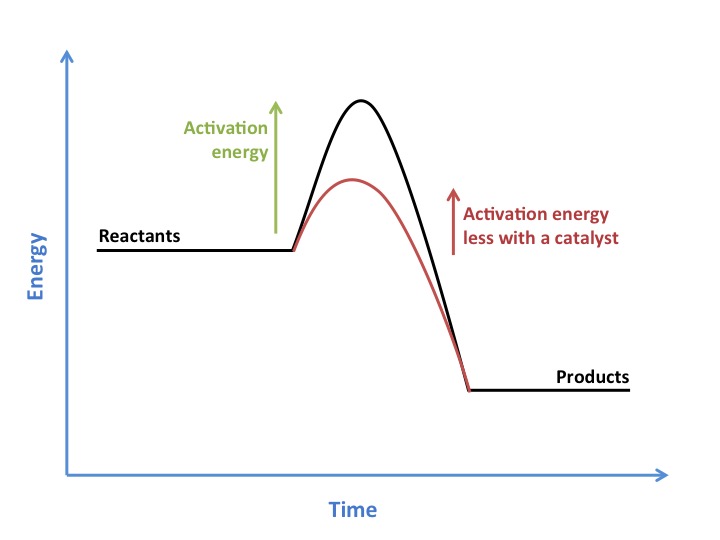

As I was thinking about Quaker process, I remembered a graph that popped up in every molecular biology course I ever took, showing how chemical reactions change energy levels:

Every reaction needs some energy (the big hump in the middle of the graph) to break down the old bonds of the reactants (left side) and pave the way for the new bonds of the products. The amount of energy to get over the hump is called the “activation energy” (green text) for the reaction. Each molecule has to get enough activation energy (get to the top of the hump) to break old bonds and form new, different bonds, making the product of the reaction (right side). If the reaction has a catalyst, it takes a little less activation energy to break the old bonds (red line).

A good example of this process in action is making cheese sauce, say, for a late-night snack of mac and cheese for a bunch of hungry twentysomethings. Cheese, milk, and butter (reactants) in a pot isn’t much to look at. Turn some heat (energy) on under it, and the bonds holding cheese to cheese and butter to butter and milk to milk start to break down. As the temperature rises (the reactants moving towards the top of the hump), cheese starts making bonds with milk, butter to cheese, and milk to butter, until every molecule is at the top of the energy hump (has enough activation energy) and is simmering into a delicious sauce (product) to cover noodles with. If you use the powdered cheese that comes with the boxed mac, it takes a little less heat to get delicious sauce (meaning some mystery substance in the Kraft powdered cheese a catalyst for the reaction).

Got it?

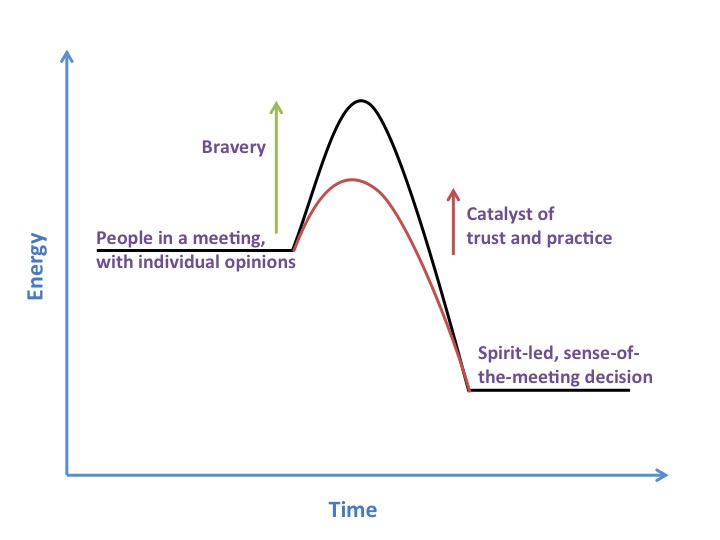

Ok, here’s the Quaker process reaction:

Each person who shows up to meeting (reactants) brings their own opinion. To arrive at a Spirit-led, sense-of-the-meeting decision, each person (reactant) has to break down their old understanding (break down the old bonds). The bravery to step into a vulnerable, open place where Spirit can rush in and open a heart or connect to a place of inner wisdom, is the activation energy of the Quaker process reaction. Each person has to reach that brave place (the top of the hump) for a sense-of-the-meeting decision to be reached (for the reaction to be completed). There’s always going to be some of that bravery (activation energy) required, but the more a group trusts each other and the more they practice being brave, the easier it gets (a catalyst for the reaction).

“Screw your courage to the sticking place”

Lady Macbeth is a character at odds with most Quaker values, but her admonishment to “screw your courage to the sticking place” is a decent mantra for diving into collective decision making. That moment, right before you open up, is terrifying—sweaty palms, racing heart, tensed muscles, wanting desperately to run away and claim you don’t need anyone but yourself.

We have to let go of a lot to be brave—all the barriers we’ve learned to put up to protect ourselves for when people let us down. Just because you’re in a Quaker space doesn’t mean you won’t feel let down again, but you're deciding that the gains from letting those barriers fall is worth the risk (trust is a catalyst). For me, there’s a particular roil in my stomach that lets me know I have to do it, I have to be brave, even when I’m scared or unsure about the outcome.

Even if you've been brave before and know it works, there's always going to be that hump of activation energy. The hump gets smaller the more you enter a brave space (practice is another catalyst), but it will never be completely gone. It becomes less like forcing yourself to do it, and more like joyfully choosing to be brave.

So how did we decide who lived where?

It took an hour or two, and some more running upstairs to imagine what a room could look like with furniture, but my housemates and I figured it out. We were brave enough to not stake a claim on a room and refuse to give it up, for fear of being pushed into a worse room. We trusted each other not to let anyone end up in a room they were deeply unhappy with.

I was scared that I would get stuck with what was objectively the worst room in the house—a tiny, carpeted middle room, without a closet, and airless even with the only window wide open. But by the second or third time I went up to look at it, I stopped feeling fear and started seeing possibilities—an ocean green coat of paint, some twinkle lights, and I could build my own clothing rack. I had time between jobs and a little extra money that could turn a boring rectangle into my oasis. I stuck with the process long enough to be open to the possibilities (you could say seeing that of God in every room?) and even got excited to live there.

My housemates and I add a provision to our Quaker process: we re-visit our decisions after the fact. Sometimes we have to live with a decision for a little while to see if it's going to work. When it doesn't, we go back and re-arrange. And yeah, it takes a long time and if that one person would just let it go, that would make it easier for the rest of us. But we made a commitment to take care of each other, and if someone is unhappy, we do what we can as a group to fix it.

We are all in this together, and Quaker process at its best embodies that. If someone is in pain, or having a leading, or a decision needs to be made, we hang together and figure it out. Until every person has found a way to be brave, through the talk and prayer and guts we Quakers call “laboring,” we don’t have enough activation energy to complete the Quaker process reaction and reach a Spirit-led decision. But once everyone gets up that brave energy, we find powerful guidance and care for one another.

So, are you being brave in your Quaker process? Are you honoring other’s bravery? Are you allowing your old bonds to be broken down and transformed?